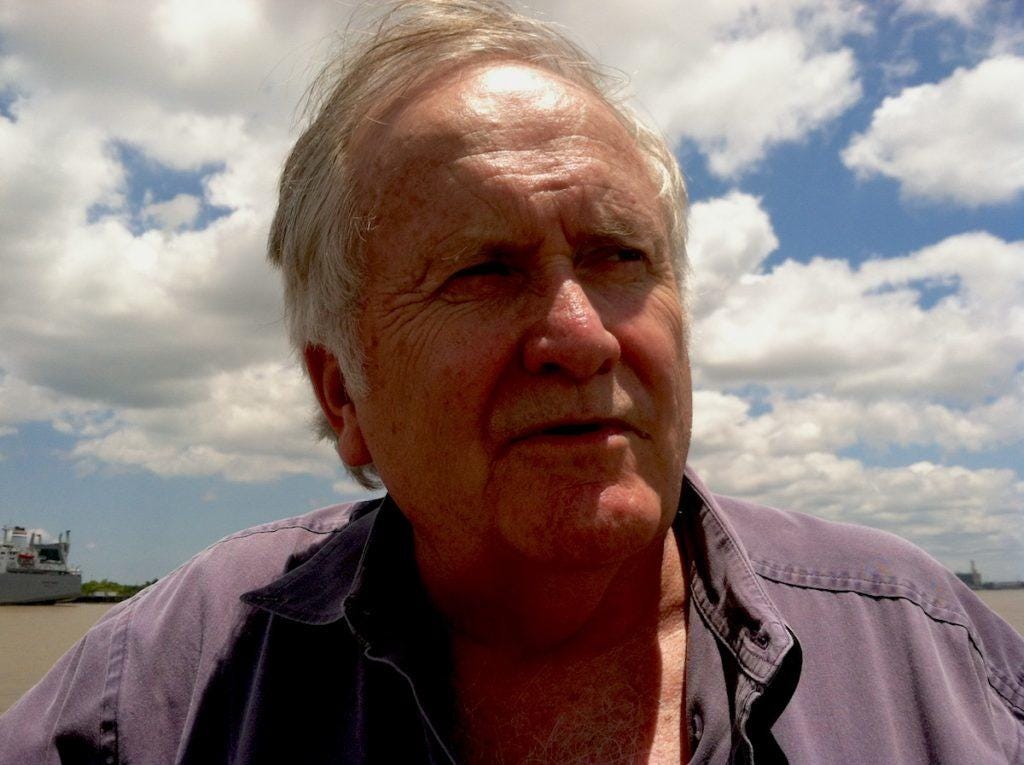

Interview with Fred Marchant

By Oswald Wagenseil. "Courage is about trying to see things as they are, and not as you’d wish them to be. We all struggle with that." -Fred Marchant

This interview is part of Consequence Forum’s Young Writers Nonfiction Project

OW: My first question revolves around a line of poetry you’re all too familiar with: “Butt, butt, basebale beast! / I fear your horns not in the least!” You’d written this decades ago in response to a bull in Roger Williams Park in Providence. How do you look upon this line of poetry now?

FM: It’s a wonderful question, first of all. And it catches me by surprise. What do those lines mean to me? There’s something slightly hilarious about the line of infatuation about the pose. I had just been reading, for the first time, Dante’s Inferno. And the teacher introduced the concept of sprezzatura. It’s like being so cool, that nothing phases you. And those first couple lines were of me projecting sprezzatura in front of my girlfriend. Because the damn buffalo crashed into the fence. So I fear your horns not in the least! So what does it mean? Well, who knows where poetry comes from. Well, part of it has to come with the joy in language. Sometimes the world comes at you with real brute force. And language doesn’t change it, but it’s a way of responding to it. The line is funny, but it’s sweet!

When you wrote that, you were attending Providence College, where you were introduced to Dante’s Inferno by Professor Rodney Delasanta. As an aspiring poet, what did you learn from reading The Divine Comedy?

I think that reading Dante at the time, I internalized the tripartite dimensions. And of course, the Inferno is spectacular, with its immense humanity and complexity. That particular moment where Dante and Virgil are climbing the legs of Satan, and boom! They’re climbing up to the mountain of purgatory. That moment was very important for me. It was such a brilliant solution to getting from Hell to Purgatory. Somewhere in that imaginative choice by Dante, there was some truth. It really had to do with my conscientious objection. All of a sudden, I think I’m doing one thing, but what I’m really doing is something else. There was a foolish thought that I’d go to the war and I’d write about my experiences. And there were a lot of things entering that formula. But that’s how I thought of it. And at the same time, as things unfolded, I realized, “Wait a minute, what the hell am I doing?” And that’s when I feel Dante is with me at those moments.

After one year of attending Providence College, you transferred to Brown. How did you perceive the students’ attitude toward Vietnam while there? What about the student activism?

At PC, I knew people who were strongly against the war. At Brown, I knew of more with several rallies at the Faunce house. There was some direct action. And I knew of it, but I didn’t think about it. At the time, I was falling in love with writing and literature. But I should’ve known better. I should’ve paid more attention to activism. It’s not for a lack of other people trying. I had some filters up. At the graduation ceremony, someone had me write a class poem for that day. And I wrote about people marching down the hill, masses of people marching. And I had this Dante-like idea of all of us, in one way or another, being shaped by this conflict. Even those like me, but I don’t know where the poem went. My life blew up shortly thereafter as I went to the Marines. I wish I could’ve been more of an activist.

As an undergraduate, you’ve mentioned Edwin Honig as a poetry mentor. What were some of the fundamental lessons he taught you?

Edwin had a wonderful sense of ironic humor. He once said at one of our workshops, “The most important thing you can do is buy a ream of paper. Because you have to revise!” I would’ve bought a ream of paper just to mess with him, but he meant it. He introduced to me the idea of writing as a process. The work of art was an ongoing life process, as much as it was sitting at the desk. Edwin knew my plans with the Marines. He didn’t approve, but he knew. Edwin had another dimension to him. He struggled as a writer, even though he was prolific. And he wrote about it. Part of his poetry was including his sense of the ongoing effort of understanding what his art was. He had four languages to begin with. English, French, Spanish, German or Italian . . . I don’t know which. But he learned Portuguese, and became a successful translator. He was knighted by the Portuguese government.

Also, he was faithful, especially to his students. I visited him before I went overseas. He was sad and careful with me. And when I came back, he helped me. He and several other Brown professors assisted with my conscientious objection. He was a big man with a very big signature. In the years leading up before his Alzheimer’s, I visited enough that we’d stay in touch. But he never stopped writing.

In 1968, you graduated from Brown and then joined the Officers Candidate Program. What was it like to write during this period of your life? And what was it like teaching on the Okinawa brig from 1968-1970?

Let me clarify a little here. I had orders to go to Vietnam and I went to be processed at a base in Okinawa. A very crusty Master Sergeant looked at me and said, “Lieutenant, I’m not going to give you a free vacation in Vietnam. So boom, you’re going to Camp Hanson in Northern Okinawa.” I joined that unit, a month or so goes on, and I get called from headquarters in Okinawa. Turns out, I was the more senior second lieutenant. I was invited to be the Deputy Provost Marshall, the deputy Chief of Police. It’s a ridiculously high job for someone my rank, but it was because people were dying so quickly.

Months later, by the time I was in the Corps for a little over a year, the whole process of applying as a conscientious objector became a writing project. I wrote over ninety pages in response to the questions about my sincerity and conscientious objection. I also began teaching that year. My first teaching assignment was suggested by the base chaplain. He said, “Why don’t you do something good?” I went to the brig and did a basic writing course about anything. Poetry, prose, anything. I asked those eligible for the courses what they were interested in. They were most interested in the religions of the war. There were a lot of Black marines interested in Muslim thought. There was also Buddhism. And I went through encyclopedias, studying as much as I could. That’s how I started teaching.

Here’s a passage from “The Return,” the first poem in your collection Full Moon Boat. The passage references your uncle, also a veteran: “ . . . The creases / of deep, dried-out arroyos reminded me / of the pack that belonged to the soldier / who hung over my childhood sleep / and taught me, before I ever understood / a word like puttee, how good it would feel / to take a helmet off, set the weapon down.”

In September of 1970, you were honorably discharged as a conscientious objector. Was it more courageous in the moment to take up the weapon or to put it down?

At the moment, I think it was putting it down. But how do you measure courage? For me, it meant, among other things, that I had a new relationship with everything in my family. The image over my childhood bed was my grandfather. What it came to mean to me, as an adult, was a sense that human beings weren’t meant to kill each other. It was this poem that made me so clear about teaching veterans, that we were in this together. There was sorrow, and we had to put the weapon down. People put the weapon down in the air, or after they get back home. But my own faith, my own faith in human beings, tells me that violence and murder is rampant throughout human history. It isn’t required. People say it’s in our nature. Well, change your nature then! People are malleable.

Reading through your works, I’ve noticed a common nod to several Greek works. Tereus, from Full Moon Boat, describes the perspective of the cruel Thracian king. Malebolge, from The Tipping Point, references a moment in The Iliad between Menelaos, Adrestos, and Agamemnon. “The Name of the Painting” from Said Not Said recalls the painting The Rape of Europa by Titian. It’s worth noting that you have studied Homer and Aeschylus when attending the University of Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought. When do you come across these works and begin writing poetry? Do these tragic moments resonate more with your poetry?

I was very lucky to have a good teacher to understand the ancient Greeks and Romans. For instance, Aeschylus. When I arrived in Chicago, I thought they had made a mistake letting me in. This was the closest I’ll ever get to Plato’s academy. These were really smart people. The teachers and students. However, I felt like I came to the right place when I took a course on Aeschylus with David Grene. We spent ten weeks reading The Oresteia, the Agamemnon only. We spent the next quarters reading the other works, but we read Agamemnon line by line. David was one of the great scholars of this ancient material, discussing this poetry. I learned to converse at that level. The conversation felt like taking this piece from the past and weighing it with human worth, and David Grene was amazing at that. He was idiosyncratic.

In Chicago, a year later, we read Walt Whitman with Saul Bellow. It was a great privilege to listen to Saul talk about Whitman. I also read Democratic Vistas, and it’s one of the greatest prose pieces by Whitman. Whitman says we need a divine literatus, the person so fully committed to the soul. And Saul would joke about that. He says, “Pay attention to the body, and the soul will follow.” I thought that was some good writer’s advice. Part of the reason I applied for the Committee on Social Thought was to work with Saul, and because I read his work while abroad in Okinawa. To answer your question, the Committee on Social Thought was scary and beautiful. It created moments where I could work with writers and create prose. David and Saul both helped me so.

In 1994, through the William Joiner Institute, you were introduced to Nguyen Ba Chung, with whom you co-translated the works of Tran Dang Khoa. You also have listed Seamus Heaney as an inspiration. What are the essential works of Tran Dang Khoa and Seamus Heaney? What’s a fundamental lesson you have learned from Vietnamese and Irish poetry?

Tran Dang Khoa was one of four Vietnamese writers who came to the Joiner Center for three months. He spoke no English, so my friend Nguyen Ba Chung helped set us up for translation. We worked on two poems, and I included both of them in Full Moon Boat. Soon enough, we became friends.

Years later, when I was in Vietnam, I ran into an American woman in Hanoi named Lady Borton. She worked for the American Friends Service Committee. She contacted me and Ba Chung, saying she made a discovery in the Ho Chi Minh Museum. It was a collection of works that Tran Dang Khoa wrote as a child, when he was ten or twelve. Chung and I, along with Tran Dang Khoa and the museum, co-translated these pieces.

In Vietnamese poetry and discourse, there is no tense. Tense is contextual. You understand the tense by what’s being said. That’s really part of the art. Showing you what’s happening, and learning to understand. I’ve tried to rope some of that into my own work. I find it thrilling how over the modern era, the Vietnamese national identity has been shaped by its poetry. I find it enormously worthwhile. It’s not about patriotism; it’s about living. So you ask about influence, and that’s one of the deepest for me. When I visited Vietnam, it was like seeing writers working in Paris in the twenties.

Now, about Seamus Heaney. In 1982, when I went back to Suffolk while working from Harvard, I met Stratis Haviaras. Stratis had a bi-weekly gathering of writers. Occasionally, Seamus appeared there. He worked late, and when I left my office, we ran into each other. I gathered the courage to ask him to read some of my work, particularly some of the poems from my first book. I loved his poetry. I loved his attitude towards poetry. He wasn’t necessarily a role model, but a model of how to be in the arts. To see the world from within the art. Interestingly enough, there’s a significant comparison between Ireland and Vietnam. Irish national identity is so dependent on artistic expression.

There was an essay that Seamus wrote called, “Feeling Into Words.” He makes a distinction between craft and technique. Technique is like practicing. But he said, “What really happens with the craft, is that practicing sometimes is pulling a bucket from a well. It’s an empty bucket every time. But then you lower it again, and something talks. And you know that you’ve broken the surface of the pool of yourself.” And that’s enormously helpful.

What are some of the most impactful moments you’ve experienced while working with veterans? Were they through their poetry or their conflict experiences?

One of the things that struck me with the Joiner Center people was their vicarious pleasure in talking about conscientious objection. Maybe some people thought it was bullshit and didn’t want to pay attention, but most of the veterans I worked with thought it was fascinating. And some people compared the “What-ifs” and such. But then, there was this other side of this debate, about having enough courage to do this. Well, yes and no. Courage is about trying to see things as they are, and not as you’d wish them to be. We all struggle with that. What I remember so vividly is when I gave my first reading at the Joiner Center, and I first met the Director, Kevin Bowen. For some reason, I felt this obligation to say, “Kevin, I’m sorry it took me so long to get these poems out into the world.” He looked at me and said, “You know, it takes us all twenty years.” I felt really welcomed into our community of citizens. The idea of veteranhood can be very stiff. Kevin and Maxine Hong Kingston taught me about veteranhood. Sometimes, everyone does not feel veteran enough. Who’s the real veteran? Who’s suffered the most?

What I found with my work with veterans, inevitably, was that they taught me as much as I taught them. They taught me, along with my wife Stefi, about the real nature of trauma. Judith Lewis Herman gave me some advice about how trauma exists. You know the Roman god Janus? Trauma has a Janus-like existence. One face says you must never talk about this; the other says you must talk about it. With trauma, Judith says you frequently oscillate between these two faces. That’s what I witnessed time and time again with these veterans. I had to learn a lot, and I’m no expert.

Your first collection of works, The Tipping Point, is renowned for your writing about Vietnam and your decision to leave. And while your writing is deservedly praised, I couldn’t help but notice that the collection is bookended with stories about your family. At the beginning, you showcase growing up with a difficult childhood in Providence, and at the end, you lament your father’s passing. What was your process in structuring the poems with this narrative?

Thank you, Ozzy. I really appreciate the careful attention. One of the things I experience with every book is the effort and desire to weave the personal and the public. In The Tipping Point, and every book onward, is that the personal is political and vice versa. How do you explore this connection? For the longest time, while working on the The Tipping Point, I thought it was through violence. What happened with me and the military was also a way of articulating or rejecting violence in my personal life too, as a witness to it in my childhood. I think the book is more complex than that now. Those themes are still there, but you’re right to note that the book moves towards a reconciliation with my father. Not peaceful, but at least through my recognition, it’s that we’re flawed human beings. It doesn’t mean that everything’s okay and that everything’s forgiven. Like that poem “Loose Ends,” and the dream I have with my father in “The Afterlife on Squaw Peak.” It is a reconciliation . . . maybe it’s too dramatic a word. But it’s peaceful. You know, at the personal level. There’s some forgiveness, but it’s not about forgiveness. It’s simply about having tea. I have a translation that I’m working on, written by Tran Dang Khoa, titled “Tea with Friends.” It’s three short stanzas, in which he says, “Okay, time to have some tea.” Then he goes, “Okay, let’s have another.” Finally, “Let’s float up to heaven.” It’s a tea ceremony about living and dying. It’s about the whole end of life, there’s something about lifespan in that poem. It’s peaceful and hubris, at the same time.

I would be remiss if I didn’t talk to you about William Stafford. You wrote and edited Another World Instead: The Early Poems of William Stafford, 1937-1947. I think it’s poetic that Stafford was a conscientious objector in WW2, much like you were in Vietnam. What are the most meaningful memories with him, as a fellow veteran and poet?

He wore his pacifism explicitly but without heroism. In terms of memories, what I most remember is that he didn’t use it as a calling card. It was much more embodied in his day-to-day life. I learned from him that way. When I left the Marines, I thought it’s not like getting a tattoo that says “CO” on it. It doesn’t last that way. You have to decide every day how you stand on this, on what’s right with the military as a killing force. He was a steadier guy than I was. He was careful about how he conducted himself in the world. That care came across in so many ways, not the least of which, was his care for his poetry. He wrote every day, beginning while he was working in the Conscientious Objection work camp. He would get up at four and write until seven. He said that was his freedom to write during that time. He got into this habit of writing something every day. He was not the kind of poet who labored on revision. He might write three to four different poems that could revolve around the same idea. In Sitka, I went to do some revisions with the one typewriter in the office headquarters, and Bill was in there, revising! He taught me a hell of a lot about how to be a committed writer, poet, and a pacifist. He still means a lot to me in those ways.

In terms of his pacifism, I can tell he was more troubled. It isn’t easy holding on to that stance. He had qualms about choosing not to take arms against someone like Hitler, or against a genocide. Being a pacifist can work against those terrible things. Towards the end of his life, he wrote a poem called “Mein Kampf.” It’s very abstract, but it’s about his own struggle, about whether he was right or wrong to do this. He came down on the side that it was, but it wasn’t easy. His son, who I know dearly, might say something else.

You have facilitated a few workshops with Maxine Hong Kingston’s Veteran Writing Group. Could you expand on the “sangha” meditation practices, and how you and Maxine structure writing exercises with the veterans?

It’s a great transition from Bill to Maxine. They both have similar roles in my life, but are also similar people. They embodied peaceful and meaningful social change. At the same time, also deliciously happy writers. They saw it as a great calling. I met Maxine in 1997 for a delegation in Vietnam to meet other writers and such and travel. A couple of years later, she invited me to the Joiner Center to lead a workshop there. I ended up doing it every Fall for twenty years, and then once the pandemic hit, it became online. I did a major amount of work with veterans at the Joiner Center.

I’ve always taught veterans—from the time at the brig in Okinawa. Over the years, I felt some earnest affiliation, and I’ve always asked myself why. The answer is that our concept of what it means to be a veteran is very limited. One of the ironies of working with veterans is that many of them think they weren’t really in the action of the war. They were in the rear and such, and I identified with that. However, to be inside a military enterprise, for a short amount of time, still has some perplexing problems for the people in it.

Maxine’s workshop began in 1992 with a similar notion. She invited self-identified post-traumatic stress veterans and a partner to come to a day-long retreat. The retreat was structured around mindfulness practices. There’s a brief sitting meditation. Then some talking and Buddhist interpretation. Some people would share how they’re doing. Then, the person who designed the topics for the day, someone like me or Maxine, would discuss the topic of the day. People would go off for an hour or two to write, followed by a silent lunch. Afterwards, people would read what they had written. There would be a walking meditation, and people would come back and respond to the readings after reflecting. Finally, another sitting meditation, followed by announcements, and we’re done. How could that mixture be important? If the hardest thing is to try and find words, and the general bewilderment of it all, and under that vague category comes PTSD. The kind of stress that haunts people. With Maxine, over the years, people have been able to find words and meanings for their experience. She had a brilliant notion that veterans came in different shapes and sizes. There were veterans in peace actions. Veterans who had gone to jail for protesting the Vietnam War. Veterans who had survived copious amounts of violence. I would say to her, “You’re my Zen teacher.” She would always deny it no matter what, but to me, she always is.

Finally, at the end of your self-interview on your website, you talk about a family tale. Your great-grandfather was a “hedge-row teacher,” secretly teaching the rural Irish without the colonial British knowing. Eventually, he was arrested by the British, kickstarting your family’s immigration to the US. In your words, how should we all aspire to be a “hedge-row teacher?”

That’s beautiful, Ozzy. Thank you. I’ve always loved the fact that I had this Irish connection. David Grene was a real teacher, a professor, but he was one who insisted that he was not a normal academic. He spent half a year in Ireland, riding horses, and he would ride horses in Chicago. He would come to class with horse shit on his boots. What he understood was how desperately we needed to understand Aeschylus, and the Agamemnon, and other works. Everyone always asks how much time do we have to devote to something really important, before we have to move to the next thing on the syllabus. I remember thinking David said, “To hell with it!” That’s the kind of hedge-row teaching that came out of the classroom.

No situation in our time is perfect, whether the situation is social, political, or historical. As the forces of history and the large tectonic shifting in society occur, people get lost and harmed. This is especially so when the lower forces are unjust. Part of the work, as I understand from my family’s legend, is that just because they say you have to be illiterate, doesn’t mean you have to be. There’s a certain risk involved, but there are hedge-rows! This is one of the ways the truth gets articulated and dispersed.

I used to think that’s what I was doing at Suffolk. Inventing a poetry center, getting into magazines, starting a creative writing program. I saw yesterday there was a talk simulcast out of the poetry center. I’ve never seen the poetry center from afar and I was so pleased looking at it. I thought, “That was my own hedge-row teaching.”

Thank you, Fred. I really appreciate your time and thoughts.

Thank you, Ozzy. It was my pleasure.

Indeed we do! "Courage is about trying to see things as they are, and not as you’d wish them to be. We all struggle with that." -Fred Marchant