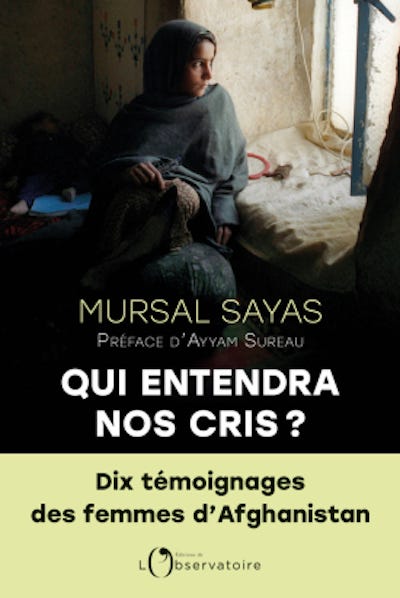

"Palwashah: silence dans l’obscurité" ("Palwashah: silence in the darkness")

From Mursal Sayas book, Qui Entendra Nos Cris? (Who Will Hear Our Cries?), a story collection written from testimonies collected in Kabul. This chapter was translated from French by Justin McGuinness.

Author’s Note: The story you are about to read is not an ordinary tale. It is the life story of one among millions of Afghan women who, simply for being women, have endured oppression, violence, and erasure. In this narrative—and throughout the book—I have intentionally avoided overwhelming statistics and figures because I believe human beings are not numbers. They have lives, souls, families, and bodies. The erasure of women is not just a humanitarian crisis; it is a threat to the healthy continuation of humanity itself because future generations cannot thrive without the mental and physical well-being of women.

These narratives are the product of my years of work at the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, in the department dedicated to the protection and development of women's rights—as well as my own lived experiences. Even as I write this sentence, the very idea of having a human rights commission and an institution to protect women’s rights feels like a distant luxury—something no longer accessible.

Think about this: How is it that in a country where the US and NATO entered under the banner of defending human rights, democracy, and women’s freedom, women were still being whipped for the slightest act of disobedience, locked away in their homes, and subjected to harassment and abuse? Hundreds of women’s organizations were operating at the time. But today, with Afghanistan handed over to the Taliban, who remains? Who speaks for these women? Who stands by them?

Four years have passed since the fall of the Republic and the withdrawal of international forces. In these four years, not a single girl has graduated from school or university. Every day, Afghan women face relentless and systemic violence—at home and in the streets. Gender apartheid in Afghanistan is no longer just a term; it is a painful and undeniable reality. Worst of all, this situation has been made possible by the silence of the international community—especially the very partners of the United States who once placed bounties on the heads of Taliban leaders, yet have now left Afghanistan defenseless in their hands.

In such a context, I’m grateful for the chance to speak about my book, Who Will Hear Our Cries? I wanted to dedicate this introduction to myself—to write about exile, about starting over, about racism, and about the foreignness in which I had to rediscover meaning and identity. I wanted to write about what happened to me, as a woman and a mother, after the US and NATO left—how I haven’t seen my children for years, and how my heart melts daily in their absence. My daughter learned to fall asleep with longing when she was only three. My son learned to live without a mother when he was just five.

But no—I cannot speak only of my own pain, when all the women of my country have been pushed to the margins. When my daughter’s cousins—just four years older than her—have been forced into confinement at home, their lives reduced to washing dishes and polishing their brothers’ shoes so they can go to school tomorrow. When nine-year-old girls are sold off under the name of marriage just to feed their family members (mostly male members), become pregnant within months, and die along with their unborn child—because midwifery education is banned and taking a woman to a male doctor is considered shameful. When I think of my children, whom I have not seen in four years and no longer know their favorite meals, I suddenly remember the thousands of children who, due to the cuts in humanitarian aid, now face poverty, malnutrition, and a slow, silent death.

I remember the days I had to fight a misogynistic legal system to get a divorce. I was insulted, humiliated. Even when the court ruled in my favor, they still tried to force me not to sign the papers. They said, A respectable woman does not get divorced. It was then that they predicted my future for me: You will be separated from your children. And that is exactly what happened.

Today, countless other women don’t even have access to a court. They face violence not only in their homes, but from a system, a religion, a society, and a Taliban regime that have institutionalized that violence. Women are imprisoned in Taliban detention centers simply for “disobeying their husbands,” without any institution to document their wounds or amplify their voices to the world. No one is fighting for their justice.

In this book, I write about domestic violence. But today, that violence has multiplied, become layered and more brutal. If yesterday, traditional patriarchy was to blame, today the responsibility also lies with all of America’s international partners—those who abandoned Afghan women to gender apartheid, and walked away indifferently from a systematic crime.

This book is for those who are silent, but still alive. For those who cannot scream. This book is my attempt to preserve their voices.

You may ask: Who will hear their cries? I still have hope. Maybe you will.

—Mursal Sayas, June 2025

(All names have been changed)

"Palwashah: silence dans l’obscurité"

Somewhere in the south of Afghanistan, summer 2020.

I was finishing my month-long monitoring mission in one of the six safe houses in Kabul whose residents were mainly women, underage girls, and a few children with their mothers. I was responsible for keeping track of how these women’s lives were evolving, and notably anything related to the non-respect of human rights. The very smallest details of their stories were recorded and put on file.

Anyway, my mission was coming to an end. To be sure that I had not forgotten anything, I came back to the office one evening to check certain documents. I went through the building, passing through the living accommodation of the women and children whom I had come to know quite well. In one of the rooms, I was struck by the vision of a haggard-faced girl whose big, dark eyes stared at the window in front of her. She crouched, seemingly plunged in the most extreme of solitudes, resembling nothing so much as a small bird with broken wings. As I was saying good-bye to the man in charge of the safe house, I asked whether I might spend some time with this particular girl whom I hadn’t in fact had the opportunity to interview. “Of course,” he replied, “we can’t refuse a professional like you such a request.” He laughed and I smiled back. Very quietly, I went back to the room where the girl at the window was living.

It was evening. The room with its blue painted walls was half in darkness. Thick red curtains stopped the light of the setting sun from entering. The furnishings comprised three sets of bunk beds in corners of the room; the middle of the room was occupied by a big red rug sitting atop the pale fitted carpet. The girl was sitting on the bed nearest to the door. She was pale-faced and her thin body was lost in folds of a pleated purple dress. I greeted her warmly and remarked on how beautiful her eyes were. Smiling timidly, she said: “But is beauty going to cure the sufferings of an unlucky girl like me?” I said nothing, my heart stopped at such a remark coming from one so young. I knew of course that none of the girls in the safe houses was exactly happy, given the appalling situations they had lived through. Such spaces of refuge were their last possible solution, where they came seeking protection and shelter. I was always struck and touched by the extreme singularity of their trajectories; all of them were marked by the same pain.

Gently, I began to talk to her, trying to note down the most important things, a difficult task for although she spoke slowly, events seemed confused in her head. I didn’t want to record her, I didn’t want her to realize that I was doing my professional duty, conducting research into her trajectory. I didn’t want to inhibit her in any way.

The notes taken during such interviews help us to put together individual accounts of the experiences of the women who have been victims of violence, merely because they are born women in an inegalitarian, patriarchal society. From the dozens and dozens of women I have listened to, I have heard the same pain and sufferings time and time again.

The room was growing darker. I listened attentively to the girl. She said she was seventeen. I wrote down her age: seventeen. Later, as I was transcribing her words, I thought of her age. Just seventeen. It was heart-breaking to hear the painful cry of this girl. An adolescent like her should have been living life to the full, in all happiness. But here she was in a safe house, her heart full of sadness. In such places, women on the run come seeking refuge.

The girl was called Palwashah. She was from southern Afghanistan, a victim and a survivor of the wars which have ravaged the country. She spoke Farsi with a Pashto accent. Her gaze and her words revealed the depth of her misfortune. She was very lost.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Consequence to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.