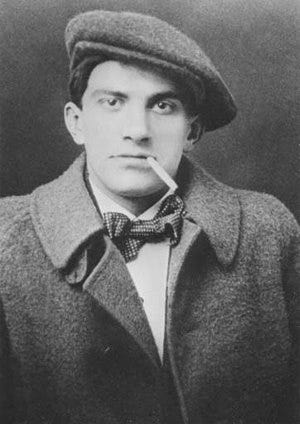

Sensuous Genius & Violent Creativity: Vladimir Mayakovsky

By Gunilla T. Kester. "Inspired by the art movement called Futurism, Mayakovsky wanted to be a spur of motivation and a visionary who conjured up a new society free from oppression and injustice."

Electrifying energy! Infectious speed! A roaring beat! Raw rhythm! Even in translation, the sensuous genius and violent creativity of Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930) soar through the page. He was both a revolutionary writer and a writer who wanted to shape a revolution. Through his writing, he wished to shake people out of their habitual frames so they could both see the world and themselves in new and startling ways. He wrote words to inspire action. In 1930, Mayakovsky begins his poem “Screaming My Head Off,” addressed to us, the people who will come after him.

You people

of the future,

Running back

over the past,

Shining a light

back over your shoulder,

you’ll probably

want to learn

about me,

Mayakovsky.

Your scholars will say

the veins stood

out on my neck

And I was pissed off!

Hey Perfesser,

get that bicycle

off your nose!(All quotes from Night Wraps the Sky, 2008, ed. Michael Almereyda)

Fueled by optimism and revolutionary spark, Mayakovsky’s poetry speaks to and of the potentially positive consequences of war. Inspired by the possibilities of a future without the oppression of the Tsar, serfdom, illiteracy, and poverty, Mayakovsky perceives himself as a leader of the millions of Russians of whom he viewed himself as a spokesperson. He wrote that his words are troops parading and he, the poet, marching in the frontlines inspecting them. Inspired by the art movement called Futurism, Mayakovsky wanted to be a spur of motivation and a visionary who conjured up a new society free from oppression and injustice. The main foundation for the changes he envisioned was the Russian people, all 150 million of them. He was pointing his finger, giving them goals and directions; they would rise and rebel. He was sure of it. We can hear it in his confident tone, the beat of his drum, and his irresistible belief in the Russian people.

In his introduction to Night Wraps the Sky, Michael Almereyda writes of Mayakovsky:

He had an early start in anti-czarist sentiment: incited by a pamphlet brought home by his sister, he participated in a pro-Bolshevik demonstration the year before his father’s death [he was 12 when his father died], became an active Party member at age fourteen, and was arrested twice before being jailed for aiding the escape of a political prisoner from Novinsky Prison.

He served seven months, much of it in solitary confinement. It is said that he started to write poetry in prison.

When he got out, he enrolled in Art School in Moscow. Why art and not literature? According to an 1897 census in Russia, about 75-80 percent of the population was illiterate. The young revolutionary believed that a picture, an image, a poster, can be worth a thousand words. Yet he kept writing! Poetry, plays, political slogans all marked by his firebrand enthusiasm and unstoppable will. He travelled all around his giant Russia. He gave lectures, participated in plays, and read his poetry to halls filled to the brim. He engaged in discussions and took questions from the audience. Once, when a small girl timidly asked him for his poetry, he is known to have answered: “Aha, you want the most interesting stuff to start right away?”

Vladimir Mayakovsky published his poem “150 Million” in 1920, right after the Leninist Russian Revolution of 1917 and the end of World War I (1919). During a time when America intervened in the Russian Civil War, Mayakovsky envisions his hero Ivan with 150,000,000 heads, an arm as long as the Neva River, and heels as large as the Caspian steppes. In this poem, Ivan crosses the Atlantic Ocean to fight a hand-to-hand battle with Woodrow Wilson, dressed in a top hat as high as the Eiffel Tower. It’s a fantastic poem full of fire and hope. How is it constructed? How did Mayakovsky summon his people to join in the revolutionary war?

150,000,000 is master of this poem.

Bullet-rhythm.

Rhyme-fire spreading from building to building.

150,000,000 speak through my lips.

It is on the circular steps

in the cobble-stone squares

that this edition is printed.

Who’ll ask the moon?

Who’ll pull an answer from the sun?

Are you fixing the nights and days?!

Who will name the lands of the brilliant author?

And so,

for my poem

there is no author.

And it has but one goal—

to shine through to the new tomorrow.Tone is one of the most essential devices poets have and probably the hardest to describe. Mayakovsky’s tone is enthusiastic and inspiring, full of energy, speed, and heat. It includes belief in numbers, facts, technology, and the future. 150 million citizens of the USSR, the 150 million Soviets of the Soviet Union will change not only Russia, but the world. Workers Unite! was its war cry.

The first thing the poet/speaker does is to abdicate his central role, his position of power and authority. The master of the poem is the 150 million souls of Russia. Then the poet describes his poem first, inventing a few words as he does it, words like “Bullet-rhythm” and “Rhyme-fire.” Whenever a writer comments on or describes the text they are writing, we call that an example of metatextuality. Such self-observation and self-awareness became more prevalent in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Mayakovsky uses this metatextual strategy linking poetic devices like rhythm and rhyme with warlike images like bullets and fire. He wants his poetry to be as violent and deadly as the Revolution and the War. These words add to the drama, and we can learn from this. When in need of a word we cannot find, we can simply make one up. There is a good American precedent of this strategy started by Walt Whitman. Whenever he needed a word, he just made one up!

Let’s go!

Let’sgolet’sgo!

Not walking, but flying!

Not flying, but lightning bolting!

Souls washed by breezes!

Past,

the bars and bathhouses.

Beat the drum!

Drum the drums!Mayakovsky identifies his role as speaker as a kind of everyman who interprets for the masses. The people’s place is in the streets, in buildings and squares, not in an ivory tower! He grounds his poem in reality, in what’s around him, and we can learn from this. I can still remember the bus stop from when I was little. Its cement bench, the smell of cigarettes, the torn newspapers.

The brilliant critic Victor Shklovsky was not only a contemporary of Mayakovsky, but a close friend. I wish I could have been present during their discussions about poetry and language. It was Shklovsky who made the remarkable separation between “story” and “plot” and showed how they function on different axis of language. The key to understanding literature must be found in its material, in language, he argued. A piece of literature is “literary” because it uses many rhetorical devices not to describe the known, but to describe the unknown. These devices can be scientifically traced and understood, he believed. Some of the devices he identified were parallelism, comparison, repetition, balanced structure, hyperbole, imagery, and motifs. Shklovsky is perhaps most known for coining the neologism “defamiliarization.” Literature is literature because it defamiliarizes the known by using poetic techniques as a means “of creating the strongest possible impression.” No wonder Mayakovsky and Shklovsky were friends!

Mayakovsky’s poem “150 Million” includes a wonderful description of Chicago, the city of electricity. Mind you, Mayakovsky is writing from his imagination. As far as I know, he never visited Chicago.

A city in it [America] stands

on just one screw,

all electro-dynamo-mechanical.

In Chicago

there are 14,000 streets

rays of the town square suns.

From each one—

700 alleys

a yearlong train trip.

It’s great for a person in Chicago!

In Chicago

sunlight

is no brighter

than a penny candle.

In Chicago

even raising an eyebrow

requires electric current.This rapid and humorous description of the modern city is anything if not electrifying. Even the mighty sun has been reduced to a source of light no stronger than a candle.

The poem continues with a fabulous description of a storm and these odd fish which appear outside of Chicago. “Very strange ones./Covered in fur./ With large noses.” Russian Ivan of the 150 million heads has arrived in America to challenge President Woodrow Wilson to a duel. How will this conflict end? It ends with a literary allusion to Homer’s The Iliad, an intertextual device:

Wilson gets up and waits—

there should be blood

but from

the wound

a person suddenly crawls out.

And how they all began to come!

People,

houses.

battleships,

horses,

all squeeze through the narrow slit.

They come out singing.

All musical.

Good grief!

They have sent from northern Troy

a person-horse stuffed with rebellion!The poem ends not with war and conflict, but in a joyous celebration of the revolution uniting two enemy countries—going global. Of course, the reality was different. Even though, we are surrounded by endless, bitter conflicts we can still take some of this burlesque optimism to heart. Mayakovsky died at the age of thirty-six. He shot himself playing Russian Roulette. He left a farewell letter. Today, most people agree that he committed suicide, but those of us who remember the dictatorship under Stalin also remember just how many poets and artists disappeared in his Gulag archipelago, and we wonder.