Whose Earth is it Anyway?

“I came, I studied, and I stayed here.” Dr. Cătălina Florina Florescu explores DACA, immigrating from Romania, and her play “La tiza/Chalk” as an exercise in acting freely as a naturalized citizen.

I was born in Romania in the ’70s during Nicolae Ceauşescu’s illiterate and devastating dictatorship. It was already terrible that we were behind the Iron Curtain, even though, geographically, we were part of the same continent. Because of decisions that took place at the end of WWII, Romania became one of the communist countries, thus made to follow faithfully the (former) Soviet Russia. Like many others, I grew up frugally, from lack of food, clothes, and other liberties. In retrospect, the most damaging effect was being brainwashed, being “famished” to have a dialogue with people from the West, being denied traveling and discovering the world, etc. So, to be alive but to feel trapped by a political regime is one of the most terrible nightmares one may endure unjustly.

My father was an avid reader of books, especially action-packed ones. One day, he asked me: “Hey, do you want to read something?”

I nodded.

He handed me a book. It was not bound, so what I was holding was a file with loose pages. I was not quite sure why it was like that, but, adoring and trusting my father, I knew he handed me something very precious. “Read it carefully, and do not tell a soul about it.” Have you ever read a book and immediately had that explosion of senses and wanted to share what you had just discovered with your best friend? Well, I could not share that with anyone. The deal was I read it, I face an eye-opening universe, but I keep quiet. My father knew that people who rebelled against the regime were incarcerated or, worse, lost their lives. He had to protect me. But, by not sharing anything, the book did not exist. In other words, it vanished when my eyes hit the last sentence on those loose pages.

This is one example of how a dictatorship squeezes the last breath of your existence. My father risked his position at work by giving that book to a teenager. It was a novel written by Marin Preda, who was a famous author even during communism, but whose suspicious death was always considered to be less than accidental or natural. My father, through his own connections, was given an uncensored version of one of Preda’s last novels, read it, and thought I was of age to decode realities. I was a curious child, in love with soccer, attending a painting club per my mother’s insistence, but I was still a child.

Years passed and whatever my father had planted when he handed those loose pages would finally resurface. I was not in Romania anymore. The Iron Curtain had become a memory. In 1998, I left my country of birth because I fell in love, got married, and I was thus introduced to the US. I came, I studied, and I stayed here. In 2016, the US Presidential Election and what followed reminded me that one must be brave to say what they think about their (about to be) elected officials because that is the least they can do. During that chaotic Presidency, I realized one more time how history is such a fragile body of hopes and dreams that, if we are not careful how we hold it, it may break right in front of our eyes.

The one-act play that I wrote, “La tiza/Chalk” was an exercise in acting freely as a naturalized citizen of this country. As an educator, history matters to me. Truth matters. Not being intimidated matters. Sadly, I could not personally thank my father for his gesture because he had died. But I was grateful that he had trust in me and gave me to read a book about censorship during dictatorship! The pursuit of honesty is something that I hold dear. Maybe I am a very naïve person, but it helps me sleep at night.

The interviews with my then-D.A.C.A. students, the articles that I found in the news about I.C.E., the harsh and inhumane treatment of people who want a better life and cross a border, the lies that are spread too hastily, all this had to be placed front and center in my play, so we start to add perspectives. In doing so, we ensure that history is never told by victors, but also, if not especially, by victims, those made to think they do not matter.

Whenever one is in doubt, I remind them about “Article 1” written and approved by the United Nations in 1948. It states the following: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

“La tiza/Chalk” was first staged and read in 2021 during the annual Valdez Last Frontier Theatre Conference in Anchorage, Alaska, where it was directed by Krista Schwarting. It was fully performed in 2023 at Yun Theater, Seattle, Washington, where it was directed by Harvey Yan. The script was supervised dramaturgically by Dr. Mona Merhi. Finally, the play is a book chapter in an anthology by and about refugees, Voices on the Move, co-edited by Dr. Domnica Radulescu and Dr. Roxana Cazan.

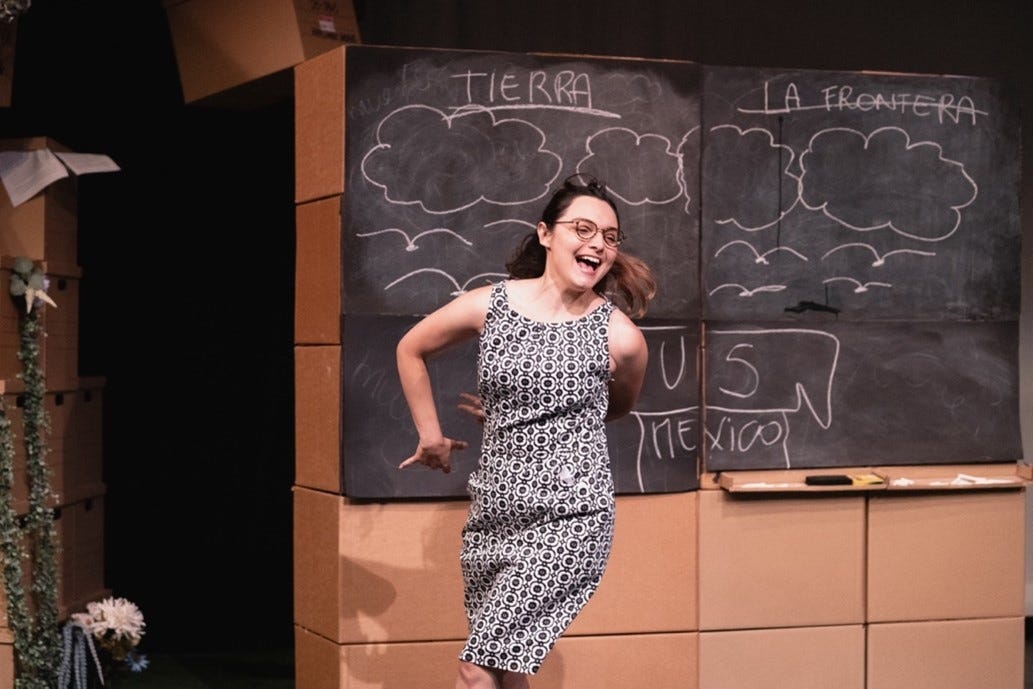

For this piece, rather than writing a script analysis, I have decided to use five stills from the performance and explain only four of them via emotions, and the last still through an excerpt from the play. Before I proceed, it helps to know that originally the main character is a male college professor of History. In performance, however, the creative team opted to have two actresses, Iveliz Martel and Xinyuan Zhang, who played various roles. The action of the play takes place in a classroom plus flashbacks. The stills, as introduced in this piece, are not in a sequential order with the script, except for the last one.

Still 1: Joy

The blackboard reads: “tierra,” “la frontera,” “US,” and “Mexico.” Clouds and some birds are drawn. The actress is exuberant. Her body language reads that unrestricted joie de vivre, something anyone should experience. The first word means “land/earth” and the second “border.” The professor writes them and crosses one out. What are professors’ moral responsibilities? The educator knows that words have an impact. To teach history as it was printed and reprinted to avoid or brush off irresponsibly over massacres, destructions, and loss, or to add uncomfortable layers/perspectives to the past? This is one of the reasons why the character is so joyful in the moment. She does not want to pretend anymore. She has set herself free, thus freeing her students to be brave and truthful like she is, especially when realities are less than ideal.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Consequence to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.